Main Second Level Navigation

Breadcrumbs

- Home

- News & Events

- News

- Dr. Andrew Baker reflects on his time as Vice Chair for Clinical Affairs

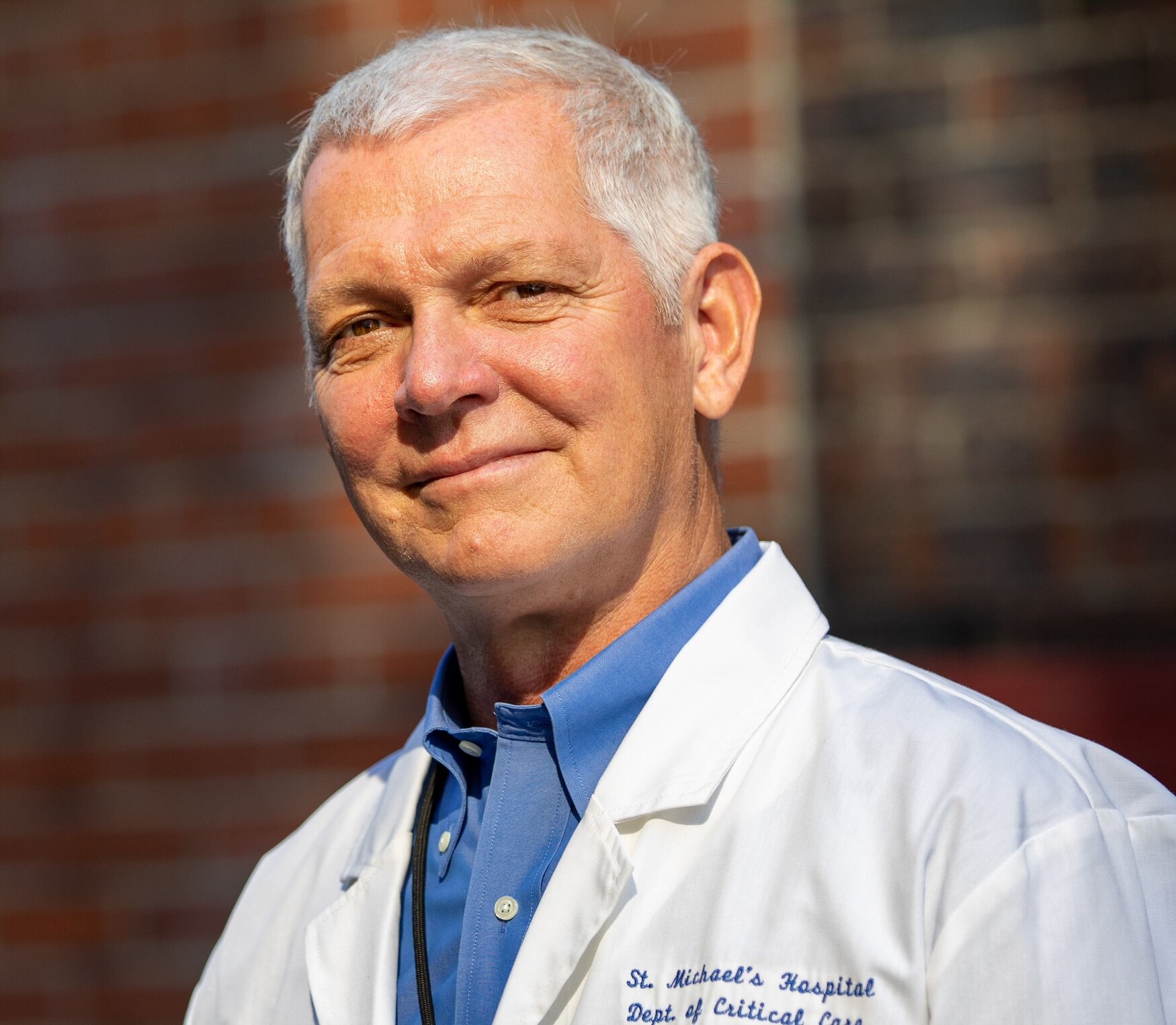

Dr. Andrew Baker reflects on his time as Vice Chair for Clinical Affairs

Dr. Andrew Baker has served as the Vice Chair of Clinical Affairs of our department since 2018. As his second term ends, he spoke with our communications team about his many contributions and leadership roles in the department.

What made you decide to take on this role?

Clinical care is the foundation of everything we do and the foundation for the university’s mission, which is to innovate and lead the development of that care.

As clinical issues continue to become increasingly complex, I wanted to contribute by studying this critical and challenging area. My goal is to help our faculty and the university mutually understand the academic value of clinical excellence.

Also, as I have mentioned at various events, including Shields Research Day, clinical excellence is the value proposition of the university, where the work of generating new research, innovation, and care is incorporated into clinical excellence and education. Learning and teaching are at the core of clinical excellence. Quality improvement is also at the core of it; knowledge translation is also foundational to clinical excellence, and, most importantly, getting the right culture and work environment is central to creating clinical excellence. These are the things that excite me.

What were some of the highlights during your tenure?

During my tenure, the COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges for our healthcare system. I was profoundly impressed by the excellence, professionalism, and personal commitment of all our anesthesia departments across the university.

Anesthesiologists played a pivotal dual role during the pandemic. They maintained essential non-COVID healthcare services, adapted to pandemic protocols, and directly supported COVID-19 care efforts. Their contributions were not just vital but truly commendable in keeping Ontarians safe during this crisis.

At the same time, anesthesiologists leveraged their expertise in several key areas: patient safety, healthcare worker protection and quality improvement. These longstanding priorities in anesthesiology proved invaluable during the pandemic response. The ability of our anesthesiologists to apply their rigorous safety standards and quality improvement practices to the evolving challenges of COVID-19 was a highlight of this difficult period.

Were there any key learnings that you’ll take with you moving forward?

There are two main things.

The first was being able to see emergent phenomena with greater clarity. For example, there was an emergent phenomenon when anesthesiologists stepped up to provide support and care during the pandemic. Individually, that was awesome, but put together, it created a system of care that was truly meaningful to keeping Ontario safe.

Also, a culture in medicine is emerging, especially with our newer generation of anesthesiologists trained in team functions, crisis resource management, communication, and even self-reflection. Again, it is fantastic at the individual level, but together, we are seeing a new culture in medicine that not only encourages equity, diversity, and inclusion but also highlights what it means to belong to a highly functioning team.

As a chief and leader of critical care, I used to say that when I reviewed issues or preventable deaths and safety situations, most of them were related to gaps or opportunities in team functioning or communication. Very few were related to their unawareness of existing knowledge. That gap is now closing a bit, and people recognize the value of highly functional teams.

What advice do you have for your successor?

Now that the pandemic is over, I’d like to see several things happen. I’d like to see a better definition of what it means to be a clinical expert so that the university and our faculty could mutually understand how to recognize that as an academic activity. I think we have moved beyond the days when an anesthesiologist who has been practicing for over 20 years is an expert because they know how to give a great anesthetic. They should also participate in quality improvement, local guideline development, team development, and innovation. I think the opportunity to codify what it means to be a clinical expert should be done and led by the university.

The second thing would be to explore innovative models of care at UofT. We should consider whether the model of having one anesthesiologist for 8 hours and one long case is the best way to manage a section of the operating room. We should consider how we leverage all the levels of care we have with the faculty anesthesiologists, clinical experts, subspecialists, and anesthesia assistants, all while maximizing the ability of our learners to participate in care to their maximum ability. There is an opportunity to invent the future of anesthesia care teams, and the university should lead in its evaluation. We should also be prepared to not get it right on the first try and to have an attitude of continuous learning.

The third thing is to start creating informal divisions across TAHSN hospital sites, which already exist in pain medicine to a greater or lesser extent. I’d like us to create interest groups in other subspecialties, like neuroanesthesia, where we could aspire to have that clinical excellence from the hospitals so that patients could expect the same standards regardless of which hospital they seek care. It would lead to a platform that supports research, guideline development, and quality improvement initiatives.

The other thing is to define thriving in another way that doesn’t just mean the opposite of burnout. The World Health Organization has defined health more broadly than just the absence of disease, and in a parallel sort of way, we all need to determine what thriving means. But be careful not to explain it in a limited way to say that we’ve mitigated all our downside experiences or risks. There must be something positive on the upside of the ledger. It must be confirmed at the personal, group, and university levels.

What’s next for you?

I’ll soon be wrapping up my tenure as the chief of critical care at St Michael’s Hospital, which I’ve held for 15 years, but I’ll continue as chief of anesthesia there.

The most exciting part of that for me is shaping the future of our department through strategic recruitment. I am so excited about getting involved and getting to know the anesthesiologists who have trained in Canada and around the world. Building a cohesive, diverse team is probably the most gratifying thing, so I hope to continue doing that. I also want to continue guiding graduates into a department that will have the attributes I am talking about.

News